Facebook flexes its muscle

The social media giant took a very different path than Google in the face of pressure to pay publishers. Australia's news consumers hang in the balance.

Welcome to The Unraveling, a weekly brainpurge that will cover current media issues and internet culture with a mix of theory, scholarship, and practice. If you like this, please subscribe and/or share it with people who might love it. THEY WILL LOVE IT. And happy 20th birthday to “ALL YOUR BASE,” which from this corner is the OG internet meme.

—————

You might have missed this important story about how two tech giants are dealing very differently with government pressure to share revenue with news publishers. Australia’s government is considering a law requiring tech companies to share profits for hosting news on their sites, and on Wednesday we saw very different reactions from Facebook and Google in preparation for this fight.

Both shoes dropped within hours of one another.

For its part, Google announced a plan to pay $1 billion in licensing fees over three years to publishers, and it was part of a larger news partnership plan to increase collaboration with major brands. The big winner in all this is Rupert Murdoch’s NewsCorp, which is the dominant brand in Australia and has been the chief antagonist for Google for years. He has curiously accused the tech company of “stealing” NewsCorp content for merely listing it in a search engine; this agreement isn’t part of that, but rather sharing profits from traffic via Google News and other news-related Google ventures.

Facebook came out later Wednesday and struck a different pose, announcing it would no longer host news content. Like, none. Australian news sites that had Facebook pages would no longer be allowed to share news content, and users would no longer be able to see news content shared by publishers. Not a total blackout, because it appears that content shared between regular users might be exempt in certain instances, but publisher pages represent a big chunk of referrals to news sites. Interestingly, this has an effect on global audiences too; users in other countries no longer have access to Australian news content via Facebook.

To understand this story is to understand the players and their power. Facebook is by far the biggest referrer for news content among the social media companies, and its power is second only to Google’s search engine when it comes to the overall tech picture. Interestingly, though Facebook is by far a more consistent referrer than Google news. But put together, these two companies are the dominant referring engines, with perhaps only Twitter representing a significant-enough blip to be in the picture.

But the difference between the first two and Twitter is important as well. Facebook and Google grab the lion’s share of online ad revenue—revenue once owned by news publishers—and Twitter is not on the same level in that regard. So news publishers, with the backing of the Australian government, are going after the source of that revenue drain and they’ve gone right to the top.

Even a day later, we have a sense of the fallout from these divergent paths Google and Facebook took. Just taking Facebook out of the equation led to a 20% drop in news site traffic over 24 hours, from Wednesday’s decisions to Thursday afternoon. That trend might not hold—people need news, and they’ll look for it when they want it—but even in the short run there is money being left on the table at a time of great instability for the news industry.

It’s important to be clear-eyed about the trajectory at work here. In this case, we’ve been witnessing the slow dismantling of the local news monopoly at the expense of social media. Local newspapers essentially owned their audience before the internet really took off during the first decade of the 21st century, but this was because local news and basic information to help people navigate daily life was harder to get in one place. This reality was a publisher’s dream, with them holding the major distribution channels for such information and having an audience with no alternatives. In turn, that was an advertiser’s dream—reliable audience consistently delivered at a full attention span.

The internet, broadly, nationalized news. I remember being a college student in the late ‘90s, marveling at how I could read news from local sources in cities far away in the comfort of my dorm room. I also remember doing a summer journalism fellowship on the East Coast and thinking how incomprehensible it was to this West Coast kid that people in that time zone got incomplete baseball box scores each morning because of print deadlines, and how I’d eventually turn to the internet to get this information I needed at the expense of the newspaper. How you did that all those years, I’ll never know. Madness, utter madness.

But this emerging online hub of information was not what I grew up with. During my ‘80s childhood, the local newspaper was a mix of local, state, national and world news because getting The New York Times in San Jose, CA during the late ‘80s was pretty dang difficult (we had complete box scores though, which is why we were the superior coast). Anyhow, just a simple web browser, backed by the power of search, created the option of choice that I had previously lacked. Thus Murdoch’s beef with Google search —a battle he did not win this week, it should be noted.

Facebook and other social sites created another type of distribution, that of a network built on social relationships, at the expense of the decline of distribution power among newspaper publishers. Person-to-person, person-to-company, person-to-bot … the sky’s the limit. But notice one critical improvement here. Google search refers someone to the news organization’s own site with a headline and maybe 1-2 sentences snippet. To the extent Google makes ad revenue off that, they truly are doing some referring because someone is searching for something specific to read. Facebook’s self-publishing features allow people to share headlines and paste in as much of the article as they want, but also that’s more of an experience it its own right; there’s an entire conversation happening on Facebook around the news that doesn’t always lead to clicks through to the news publisher’s website, but Facebook is reliably making money off it anyhow.

News production is at the core of both models, in the sense that both Google and Facebook need news content to exist to have either search or news-driven conversation. But news is expensive to produce, and ad revenue has been dropping. It’s a bit of tragedy of the commons at work here, with the tech behemoths depending on news they don’t fund in order to provide value, and the commodity being exploited is on the decline as a result.

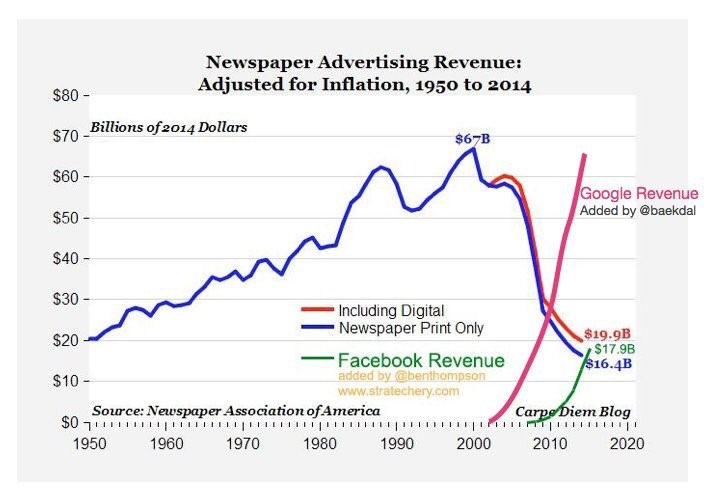

To wit, the infamous OH MY GOD graphic (as I like to call it in class) from the Newspaper Association of America that shows the steep drop in ad revenue for newspapers relative to massive gains made by Google and Facebook (latter extra work is done by Thomas Baekdal):

Those are dollars adjusted for inflation, but more importantly, those are apples-to-apples dollar comparisons between newspapers and emerging digital products, charted through the middle part of last decade. It’s a trend that has only gotten worse. Google revenue alone is close to the $70 billion peak of the newspaper salad days.

Bear in mind that, at its peak, ad revenue accounted for about 70%-plus of revenue at a typical newspaper. Taking that kind of money out the newsroom comes at a cost, the kind that can’t be made up by digital subscriber gains alone. In the face of this, newsrooms have had to make massive cuts to stay afloat while still producing news to meet demand from an audience that wants all this stuff but is less aware of the enormous cost for producing it. The debate for the past decade is to what extent these tech giants making money off media content they don’t produce should share revenue. What Australia is trying to do is force the two biggest beneficiaries of the digital ad revenue shift to share some money with those it relies on.

It’s a story that’s easy to miss, so it’s worth underlining here: Facebook and Google compete with news organizations for digital ad revenue, but these camps are partners for content delivery in some sense. Google’s product is usefulness, put in broad terms, and without news organizations it has less value. Facebook arguably relies less on this even as it benefits from it, though on a smaller scale people still need something to talk about. Given that, you can possibly see why the companies took different paths. Facebook might have some reason to believe it doesn’t need the news.

The companies are going their own way, but Facebook arguably is right on the substance. The proposed Australian law is a giant giveback to NewsCorp, which has tremendous influence in the country’s news ecosystem and has a lot of influence with the politicians working to pass this regulation but has seen its revenue eroded by tech companies. The law is being sold as saving news, but on its face it appears to be an attempt to reconstruct a dying monopoly for a wealthy political patron at the expense of innovation in media. We do have to find a way to make news—particularly local news—sustainable, but this is just a redistribution of money that does nothing to address the problem of dwindling audience and trust in news that also are factors in the decline of the news business.

Still, there are a couple lingering questions, though, about the path Facebook took now that it’s fully owning its ascendant distribution power. The company might be right on this stance, but this incident surfaces a deeper set of background problems that come with dominant companies at their scale.

First, what can we say about a company that essentially possesses a news kill switch? It’s a bit troublesome, isn’t it? On the one hand, you have to admire a company willing to tell Rupert Murdoch or any other powerful person to go to hell. Not my deal, but game recognizes game. But on the other hand, that Facebook could decide this on Wednesday and implement it on Wednesday …. whew. It was already in the code. They’d prepared for this moment, and they pushed the button. This is where the fun begins.

Can you still get Australian news? Absolutely. You don’t need Facebook for that, and by the way Google will be happy to help. But it’s important to see the internet beyond your own use lens. For many people, probably people older than you, the combination of Facebook and email are the internet. They are a primary agenda-setter, and even to the extent that people use other sites, that is set in motion by Facebook.

Related, but also worrisome, is that in this scenario it is Facebook that defines “news,” and in that scenario there is always collateral damage:

Hanson-Young in this case wasn’t just referring to health news from media outlets, though that itself is pretty bad in the middle of a raging pandemic. In this case, Facebook blocked news from sites dedicated to dispensing public health information. If you need a U.S. analog, think about them blocking news from a page run by your city’s local health bureau, or the CDC. Vaccine news, health guidelines, stay-at-home orders. Is that public information or news? It’s both! In this case, Facebook decided there was no daylight between government news and professionally-manufactured news.

This specific grievance probably is something that will change. It could just be Facebook making a point to government news sources about knowing its own power, or it could be an overaggressive use of an algorithm (“Alexa, ban everything titled news”). But either way, the power about getting to define what is news, under threat of regulation, ultimately rests with the tech company if it doesn’t want to play ball. This is little different than the decades-old debate about whether the government ought to be licensing journalists. Who gets to decide what is news, and what is journalism? And do we want the very object of accountability to be the decider? Well, as a major distribution point for news, Facebook gets to decide.

Raw politics, or raw exercise of power, or not thinking too deeply about what the news is—regardless of the motive, what happened here shows the practical effects of Facebook’s amassed clout. It’s something we should all be concerned with.

Second, what will replace the news on Facebook? It could be more cat videos or kid pictures. But given Facebook’s unreliable track record with squashing conspiracy theories, antivax and political disinformation, the real worry here is that the site will be less populated with professional news and more populated with junk. The platform is a cautionary tale for what flourishes in vacuums.

It’s not like I’m siding with NewsCorp here. The company isn’t always a great actor in the news space and Lord knows Fox News has had its share of conspiracy-theory-mongering in the evening pundit lineup. It also has a track record of using its news products to selectively frame information in the U.S. and the U.K. to achieve ideological goals and self-interested policy goals. This latest dustup is a good example; the proposed law in Australia is being driven by NewsCorp and will primarily benefit them even as it’s being sold as beneficial to all. NewsCorp also has been beating the tech-regulation drum in the U.S. for a few years now through its Fox News product suite, and if the Australia windfall is any indication, it stands to benefit from any policy change that reduces the power of tech companies and shifts funding back to news organizations.

That said, I trust NewsCorp news more than QAnon conspiracy theories dressed up as news on social platforms run by intellectually uncurious managers. It’s not like the emerging tech powers have done a great job giving us a great news delivery experience. At least NewsCorp products have a methodology I can follow and critique with built-in accountability on the daily. Coupled with a mass audience and desire for access to cover the powerful, NewsCorp is going to mostly play within a certain set of rules so that it maintains that access. Facebook without NewsCorp content and populated instead with disinformation and propaganda is much more worrisome and destructive, at least for now.

The parameters on this question are complicated. Self-governing democracy requires access to reliable and trustworthy information. The government, any government, is capable of becoming a platform in its own right, but it has long depended on third-party credibility to get its message out. That is, people encounter information straight from the government in strategically different ways than they do from a news organization that has sought to verify and skeptically interrogate information before publishing. Losing the news might seem like a boon for a rising autocracy. But it doesn’t equate to trust, let alone a stable society. The news might give leaders heartburn, but we still need it.

In that sense, Facebook holds a lot of cards in this particular scenario. The public health information complaint from Senator Hanson-Young might get fixed, but it shows the precarious position governments are in relative to Facebook’s accumulated power. There’s a regulation thread to pull here if leaders can get on the same page. There also is the threat that coordinated action globally among democratic governments can collectively force Facebook to bend the knee; Australia is a drop in the bucket, but a string of losses in other countries whose audience Facebook needs is is a whole different deal.

Jeremy Littau is an associate professor of journalism and communication at Lehigh University? Did you like this? Please share and smash that subscribe button. Find him on Twitter at @jeremylittau.