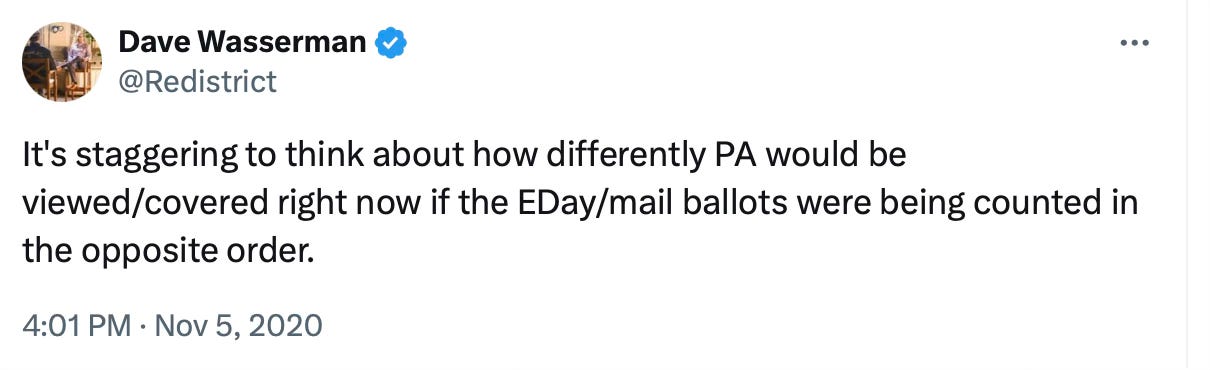

I think a lot about this old tweet from election data guru Dave Wasserman:

This post is a plea to consume information with care tonight as you watch election returns come in.

What Wasserman noted above is consistent with what I teach at Lehigh about the power of the news to frame information in certain ways. In the case of election night reporting, stories are to an extent artificial constructs. Sometimes news stories are more solid than others because they have the benefit of time and thought, but in breaking or developing news situations news should be consumed with some care and contextual thinking because our understanding of the truth is evolving and more subject to revision as we get more information.

News narratives are built by turning lists of facts (data, quotes, information) into stories, and those individual stories collectively across media become meta-narratives that take on the quality of truth if we aren’t careful. This is the product of reporting. Journalism isn’t a list of facts. It is an attempt to make meaning out of facts. But at the same time, news audiences are consuming news alongside facts they ingest and news they consume from other sources, some of which is solid and some of which is junk. Given all that, it’s easy to distort understanding in a breaking news environment.

In a slow-developing news environment, journalists have time to get around a story as much as possible, and they try to build in as many of perspectives as they can. But as news is unfolding, it is more difficult. Perspectives built on incomplete data are not reflective of the full reality, but the public is hungry to know more and so it incentivizes news organizations to report the news as data comes in. This means that news narratives on election night are artificial, yes, but also being revised, updated and in some cases subverted as we go. It’s why we should both make and watch the news with some care and eye on complexity. When a narrative changes or is subverted, that is not a shift in momentum akin to Steph Curry raining threes in a Golden State Warriors game to help erase a 20-point deficit.

The complication is that when journalism is built by election results data (actual votes, not polls), it is built by default by a factor out of a journalist’s control: how the data comes to us. Additionally, it is built by how journalists choose to sort data and report it. Some examples:

Election Night: Why do we even have it? Why is it an all-night TV fest rather than just waiting for complete results? To the extent it feels like sports coverage, that is narrative taking hold. As states get slowly called or even state results slowly trickle in, it has the feel of momentum.

The order data comes in: States report on their own schedule, at their own pace. Within states, some counties report at their own pace, and within counties it’s made up of precincts that vary wildly. What comes in first sets the tone for how you see later data.

The random order of state calls: It’s built on data. When a news organization feels confident enough, they’ll call a state. That all 50 states aren’t called at once creates artificial feelings of momentum.

A thought exercise: You can play with the problems that come with the bullet points above by reimagining how an election night news narrative would look if outlets reported results by region, or alphabetically. How you prioritize a method for reporting the data determines how your story starts, and how it unfolds. But election night is based on data flow that is out of your control, and so the narrative you make is hijacked by an externality.

In 2020, I went to bed on Election Night when the narrative was “Trump could win this.” But on its face that is either a true or false statement, not at all congruent with a subjective statement that uses a word like could. The votes were already in, and he either won or didn’t. The only reason to use subjective language is because we were dealing with unknowns about data reporting, not the actual data itself.

By the next day, it became clear that wasn’t true; the race wasn’t called but the data said Trump was likely to lose as more votes got counted. But on election night itself, a statement like “Trump could win” was as true as could be known at the time based on incomplete data. You see the rub? It was true in the sense that it was the best version of the truth known at the time based on data released to the public, but the complete data set made it objectively false. We just didn’t have access yet to the latter.

The results are the results. They have a truth on their own. The Truth. The final tally is the story, and yet journalists are tasked with telling a story before that because news cycles and public demand. The idealistic and perhaps most democratic way would be to say we just be patient and wait for the final story. But the public doesn’t want it that way, and truthfully the data are public enough that non-journalists will make it available regardless of whether news organizations took an all-at-once approach out of caution. So you report as best you can in hopes that sunshine is the best disinfectant of bad information

Journalists make sense of things in real time, but it’s an artificial construct. So, does this make the narratives bad? No. It means the public swings of attention and emotion could be greatly helped by some media literacy here, and news production processes that highlight what is going on beneath the raw data.

Think about what happened on Election Night in 2020 and how a regular person might react to the news as it came in. Trump went up big early in the night because mail ballots were used at extraordinary levels due to the COVID pandemic and because the initial vote returns from many states were built on in-person votes that were heavily Republican because Trump had spent months calling into question the validity of mailed ballots. So, if you didn’t know this context of a party differential on voting methods, it would be understandable to feel like Trump had momentum; he was getting a lot of state calls in red states he was always going to win and had big leads in blue states, leads built on in-person vote tallies. But the momentum was artificial; there were always the same number of votes in the tally, but the order in which we got them created impressions because in a lot of critical states the mail ballots were counted last. A consistent news user would have had months to learn from previous reporting that the mail vote in many, many states was going to skew heavily Democratic (media doing this education work before Election Day called this the “red mirage”). The “comeback,” which really isn’t a comeback so much as tallying votes already cast, was inevitable. But unknown was how big the comeback would be, and even the knowledge of what was to come was in opposition to the feeling many had that Trump was up big and had momentum. And for an inconsistent news user without the context at all, it might feel like something was awry.

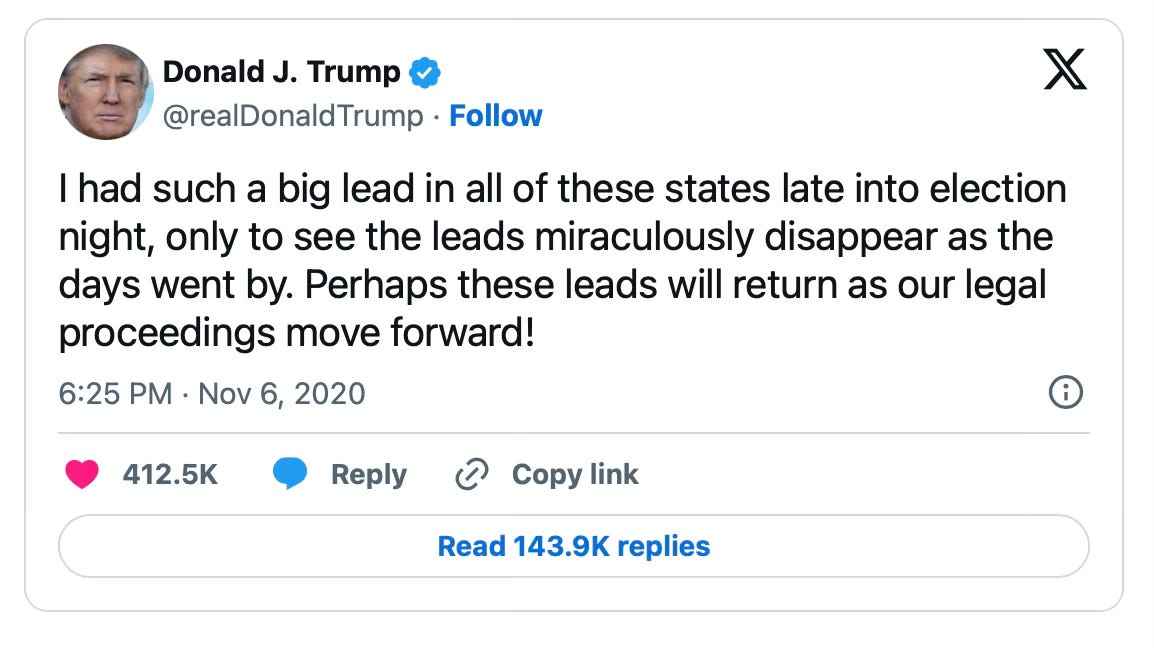

Trump himself tried to exploit this by trying to cast doubt on the whole process. He had a big lead and didn’t, and so he falsely portrayed that as fishy:

Reader, those leads did not return and we all know how that ended. We dealt with false claims of election fraud for about two months, typified by the Trump campaign losing about 60 lawsuits because it could produce no evidence of fraud. It all culminated by a Trump rally in D.C. on January 6, 2021 that served as an incitement to get his supporters to try and occupy the Capitol and force an overturning of a free and fair election. Someone died in that process, several Capitol police officers were injured, and it ended up being one of the more horrific moments in American history. All based on a lie that exploited a false sense of momentum built on a lack of understanding on how ballots are counted.

This is the problem with news narratives if we don’t engage with them critically. News narratives shape how the public sees stories such as the counting of all votes after election night. Journalists have a specific role here; they need to report the data but also to help the public understand the events that shape the data, because if not it creates a vacuum that allows someone to sow doubt about a normal process.

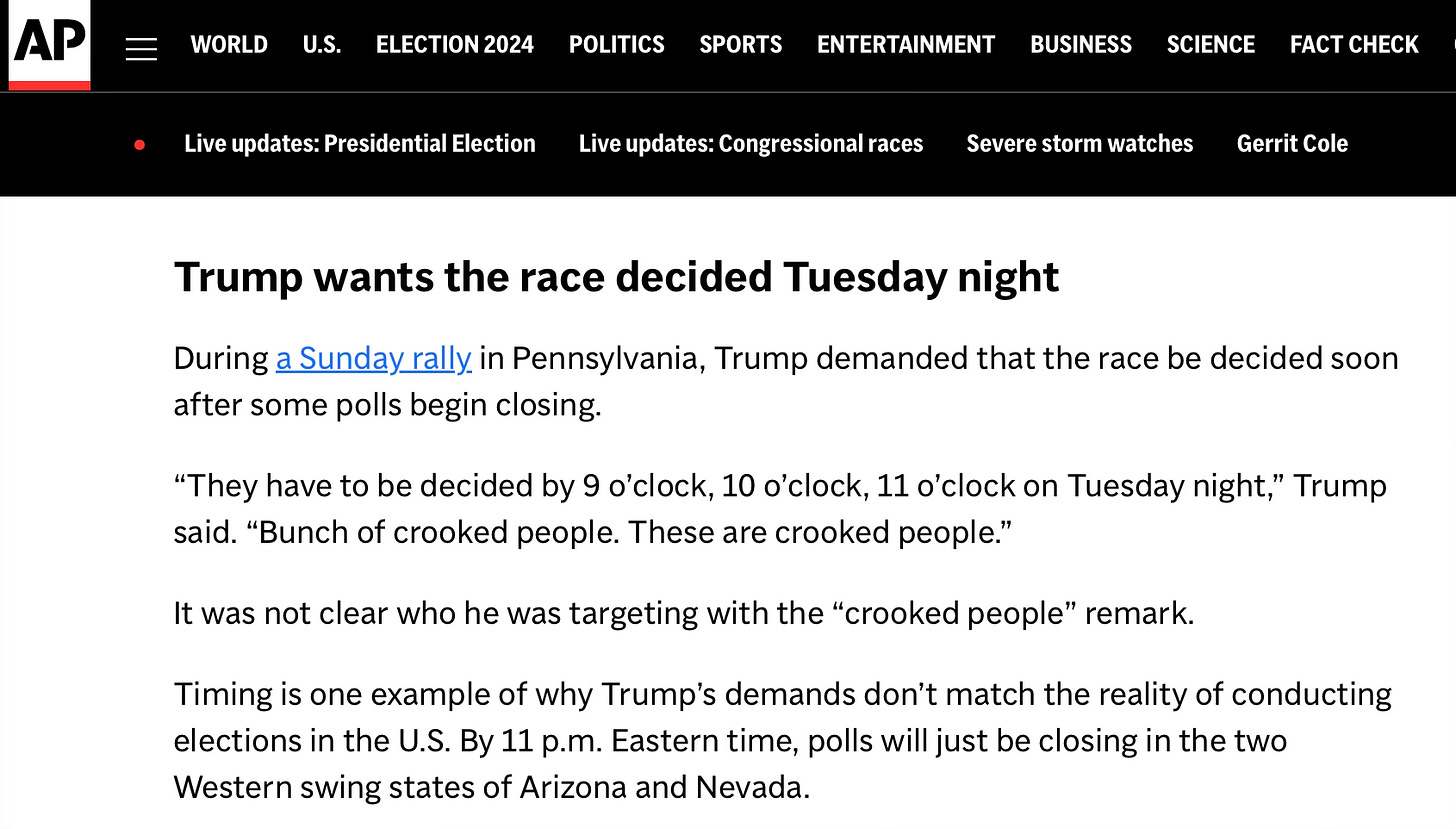

By the 2022 midterm election, many news outlets had learned from this process, to set expectations appropriately and educate news consumers about the vote-counting process so that they could understand vote results in context as they came in. I suspect they will need to do even more of this in 2024 with Trump already making noise that sounds a lot like 2020. Here’s a clip from AP coverage of a Trump rally last weekend:

The reason I teach my intro course the way I do is to help students grapple with how to approach news better and how to read narratives better. News coverage is never going to get be perfect, but there are honest methods and dishonest methods as well as good context and bad context. Good coverage will be as accurate as possible and give news consumers the appropriate cues about what is a settled narrative compared to one that is in flux. By the end of the week of the November 2020 election, the narrative was settled. On election night, it wasn’t. The best news coverage gave readers what they needed to understand this.

What people often declare media bias is often just incomplete narratives because either the data isn’t final, or because journalists can’t verify something at the time you go to press or on the air with what you know. When he spoke at Lehigh several years ago, Watergate reporting legend Carl Bernstein called the journalist’s goal reporting the “best attainable version of the truth.” But the weakness of this is that it makes incomplete news narratives ripe for hijacking by bad actors. It’s what’s happened in the run up to the January 6 insurrection in 2021, and the Trump campaign has already telegraphed that it will try the same playbook again should the election not go their way. That this is already a known post-election strategy should be reason to report with caution and nuance (and to include that strategy in the reporting so news consumers are ready).

My hope today is that news organizations will help news consumers understand the uncertainty involved in bringing us the news tonight, that the story is slowly evolving and somewhat random based on how vote totals get reported. And for the public, that perhaps they will not treat results coming in like it’s a basketball game, with back-and-forth lead changes. All of that is artificial; the votes are the votes, and we just need to count them.

Jeremy Littau is an associate professor of journalism and communication at Lehigh University. Find him on Bluesky for short-form commentary and analysis about digital media and society.