Privacy for thee, but not for me

Maybe we don't care enough about adtech data privacy to do something about it, but Apple is betting that informed consent is a better future than the cyberpunk version we have in front of us now.

Welcome to The Unraveling, a weekly brainpurge that covers current media issues and internet culture with a mix of theory, scholarship, and practice. Now planning to attend Lehigh commencement in person!

—————

Apple is about to do a major throwdown—those are still a thing, right?—on data privacy that will have big consequences for companies that rely on data collection to sustain themselves.

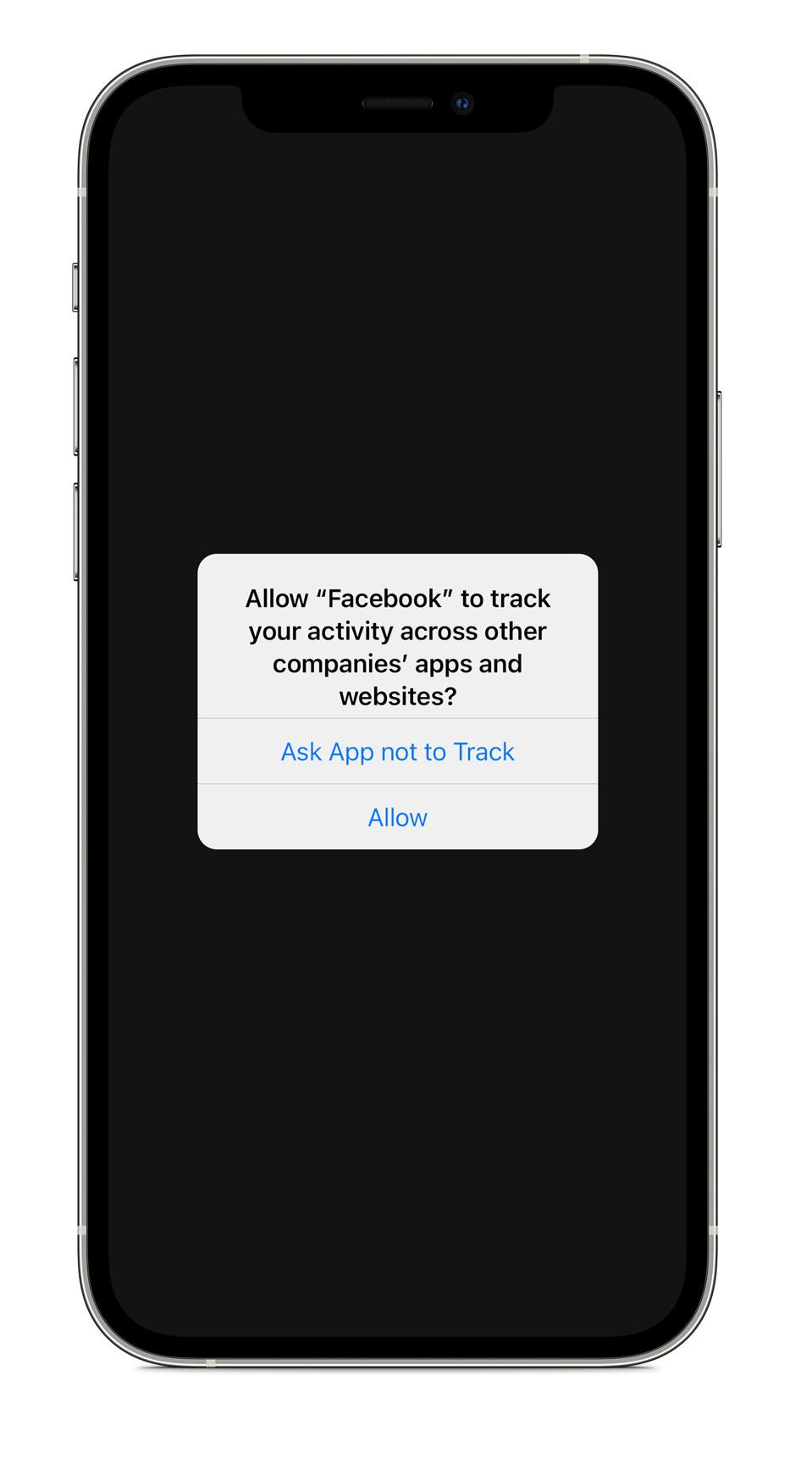

Coming soon in an iOS 14 update will be a requirement that forces companies to provide information about data collection in a popup window when someone opens a given app. This quick-hit information is supposed to give a user some sense of what data is being collected about them and asks for consent, with the stated intention of helping a user make informed choices about apps they use. This is a big, big shift from how it’s done now, which relies on some mix of the honor system and Apple policing app makers to be sure they are following the rules (and in Googleland, it’s much more of a free-for-all for Android users).

Apple can do this because it controls its App Store from upload to download, and thus is forcing companies to participate in what it calls “App Tracking Transparency (ATT)” by making them disclose data mining efforts. Crucially, this is opt-in for the user, forcing the app to get explicit consent to be tracked across sites, and that is not insignificant given that the average app has an average of six trackers embedded.

This is just an extension of a drum the company has been beating for a few years now. CEO Tim Cook gave a stirring-for-him speech to European privacy commissioners in 2018 that called out abuse data collection processes and has staked much of the company’s brand image on the notion that it is paying attention to privacy in ways others are not. It’s worth watching this short speech just to get a flavor of what he’s talking about.

To wit:

"Taken to its extreme, this process creates an enduring digital profile and lets companies know you better than you may know yourself. Your profile is then run through algorithms that can serve up increasingly extreme content, pounding our harmless preferences into hardened convictions. If green is your favorite color, you may find yourself reading a lot of articles—or watching a lot of videos—about the insidious threat from people who like orange.

It’s worth noting that Apple has some stake in the privacy wars to come if for no other reason than mere differentiation, though its incentives differ compared to another hardware manufacturer such as Google. Apple does dabble in services and products, but those efforts are so sandboxed given Apple’s general views on owning its own experience that most of it is blocked off from content you see. Thus when it claims there are limits on what they do with their data, the products and services Apple offers bears that out somewhat and it exerts much more control over third-party developers that publish apps in the company’s ecosystem. But user experience is part of Apple’s selling point and drives hardware purchases, so it’s logical to see that they have some vested interest in making sure users want and like what they buy. Call it a brand calculation, or what they call a “curated experience,” but either way Apple has sold its lockdown control as a good thing for consumers.

Notably, Apple has chosen at least rhetorically to go after a specific framing of data and privacy: the collection of unneeded data and the sale of data to other companies, the latter of which is big business to some of the company’s rivals.

Thus we can look at Apple’s stance through the lens of self-interest, yes, but also with some nod that they are talking about privacy in qualitatively different ways than competitors. I would describe the company as a hardware maker that derives a lot of value from a tightly controlled experience. It approves apps before putting them on the store, it puts walls around certain things the company knows about you, and generally speaking they don’t allow things on their mobile systems without looking at it first. Their nearest competitor analogue would likely be Google, which also makes wildly popular hardware but has more open standards for apps you can install, but Google also has services that don’t depend on you owning an Android phone for them to work well.

In that sense, Apple is in a unique position to call shots and upend whole markets that need large numbers of iOS users in order to survive. You can hear the social media platform freakout out from here.

Most of the logic on Apple’s forthcoming privacy moves have centered on the effects of adtech. This would include digital advertising companies that depend on data collection and tracking in order to serve up customized ads in ways that are highly targeted.

One way of thinking about this is that if you subscribe to a magazine such as Vogue, you are going to get a certain type or class of ads. Largely ads for companies and products for women in a certain age demographic. Certainly men and others outside that demo do read Vogue, but this is a blunt-force form of ad buys driven by bell curves. What can we say about the bulk of Vogue’s audience? That right there is your advertising sweet spot.

Targeted digital advertising is different. It rushes right past the question about audience generalizations and instead is predicated on you, who you are. In this kind of market, ads are served up based on your interests and demographics, and instead of relying on broad market research with aggregate statistics it instead uses data collection to know this information up front before serving up the ad. So an advertiser selling, say, makeup can preselect which readers get an ad based on characteristics already known about the user rather than using market research to determine that most readers are interested in makeup. Maybe they specifically target for age or gender. More invasive, maybe they know you’ve been googling makeup products. Most invasive, maybe they have access to facial recognition data that tells them your skin tone so they can make personalized suggestions.

Welcome to hell. Or heaven, if you like that kind of thing.

Targeted digital ads are a hell of a deal when it comes to return on investment (ROI). You don’t want to waste money selling a product to people who never wanted it, and old school advertising in traditional print, radio and TV did just that. To be fair, there wasn’t really another way to do this until Mark Zuckerberg and crew perfected invasive data collection and created a whole new advertising market.

That’s why I tend to refer to social platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and the like as adtech companies with data collection bootstrapped on to social sharing features. From the user side it’s all about posting an interacting, but all of those actions are just data and in aggregate the users are just a new market for advertisers to talk to. What Facebook has assembled is no different than the newspapers, TV stations, radio stations, and magazines before them: an audience that is here for the content and ready for your advertising pitch.

It’s important to see that these are different narratives about the same platform, app, or product. But your sense of what the product is can depend on which point of view you take. Am I just doing it for the Gram or have I become a market research singularity?

There’s a reason Facebook in particular has been scornful of what Apple is about to do, positing that the changes would destroy its business. It might well be the case, but Facebook has a track record for hyperventilating about nothingburgers and has been adept at adapting. This is a game of cat-and-mouse, with Apple trying to put fences around Facebook’s endless data graze. In that sense, it is a clash of technology interests with users in the middle. Bear in mind, Apple’s plan is to supply users with information that allows them to make informed choices. They might still go along or they might put walls up around it. Apple isn’t banning Facebook from its platform, just requiring informed consent. But Facebook is an advertising vehicle dressed up as a social platform, and any change to data collection affects its bottom line.

I don’t want us to sleep on one critical argument Cook made in the speech above. Adtech clearly is implicated in some of the curbs on data collection, but he also noted that tracking in general is being used to determine content decisions on these platforms too—what news organizations or algorithms choose to publish or surface, what social platforms choose to deliver to you, etc. Cook noted that data isn’t just about ad surveillance, it’s also about how conspiracy theories and toxic content reaches you on the same platforms doing ad surveillance, and that in truth these are not at cross purposes. While the purpose of content and ad delivery are different consumption processes, from the perspective of a Facebook they are correlated functions and built on the same tech architectural premise: data collection in the service of customized experience and wired for your engagement. Yes it’s news vs. advertising, but as a Mizzou j-school mentor once told me, “It’s all persuasion, baby.”

So while the adtech implications are getting the buzz, there are democracy-warping implications to surveillance tech in general and it means that any walls around data collection have implications beyond ad delivery. Apple is using its market power to force at least a conversation about what is gathered and some disclosure about how data is used. It’s a unique position that only Apple and Google are in a position to make, because they make the lion’s share of the hardware people use to access the mobile internet in the U.S. Yes, there are all kinds of monopoly and anti-competitive questions here that are worth raising, but I prefer it when my tech giants are fighting one another rather than us.

So Apple’s impending Datageddon seems from this corner like a choice-driven future compared to one that is happening on background. It might end up that we don’t have a lot of feelings about data collection, on the assumption it’s all been happening and we don’t have much say in that. But the layer peeled back here at least says they should tell us what they’re doing with our data, how they’re doing it, and whom they will share it with.

It might be that we can’t fight this future. I am more optimistic about human potential when we finally have had enough of tech bros behaving badly, but it’s hard to take up the cause if we don’t at least know what’s going on.

Jeremy Littau is an associate professor of journalism and communication at Lehigh University. Find him on Twitter at @jeremylittau.