The visual information war

The most serious battle is happening in Ukraine, but for those not feeling the violence there is a war for hearts and minds in public opinion. In the social media age, we are doing the fighting.

There obviously is a bloody and brutal war happening in Ukraine right now, and the citizens there are paying a heavy cost we cannot imagine. But in the time of mass media, wars are also a battle of information. Policies that support war efforts, or support our allies’ efforts, rely on public support. That means how media, governments and societies frame conflict is important to coalescing public opinion.

The first Gulf War had embedded reporters and Pentagon-produced videos with cameras on bombs to frame successful strikes that stripped blood and loss of life from the public’s visual surveillance of the war. Other wars had field reporters, and that coverage could at times be seen as boosting support or, in the case of Walter Cronkite’s famous conclusions on the Vietnam effort, tanking support.

World War II featured film reels that functioned as types of propaganda about the status of the war (recall that at this time television was not yet widely adopted in households) and infotainment such as Disney cartoons to prop up domestic efforts. Just look at this below. It’s wild to think this came from the same Walt Disney Co. that now goes out of its way to offend nobody (intentionally, at least).

This is not to undersell the real violence and tragedy in Ukraine. It’s to point out that the war of information exists alongside that violence in ways that embolden leadership or can make us war weary. And that public sentiment has real effect on how we act as a global community.

The Ukraine invasion is showing us another wrinkle to that mass media war, one built around conversation. It’s not just governments selectively showing us imagery or sharing detail. It’s not just journalistic coverage shaping how we see what’s going on. Social media is a place for showing solidarity or signaling our own position on the issue, which is about as much as any person not in the region can do right now.

Some acts are simple, such as changing your profile picture to a Ukrainian or Russian flag. But platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok also have robust resharing tools, which creates potential for garbage-in-garbage-out distribution at the point of user. It is in this space that Russia has been operating for almost a decade unfettered, and before you think this is a RUSSIA, RUSSIA, RUSSIA post, bear in mind that regardless of the measurable impact it’s undeniable that Russian propaganda outlets and bot armies have been seeding the ground on social networks, often unknown to an uncritically consuming public. This content is already out there. It has already shaped us in some way or another. It’s the basis by which we confront new information about Russia and its current aggression.

In particular this past week, I’ve been keeping an eye on visual media because it has the most potential to lie to us. Cropping on images, swift cuts on video that remove important context, staged videos that look real because they reflect the raw feel of live user video … all of these are rocketing around social networks and getting uncritical reshares. Some of this is intentional propaganda from one point of view or another. Some of this is just people trying to grab attention, knowing that our fucked-up ad economy rewards clicks and traffic numbers and not verified information. NPR had a good story on TikTok in particular and I’d recommend you look at it, because this is what the teens all around you are seeing.

I’ve been clipping images for my mass media introductory course this past week, amassing a bunch of small instances of the way we do information during times of war in the social media era. These are images I’ve collected from friends’ social media shares (my method is to clip it if I see it repeatedly, because that’s a sign of virality). They are examples of how difficult it is to assess visual information about Ukraine right now.

Phone screen

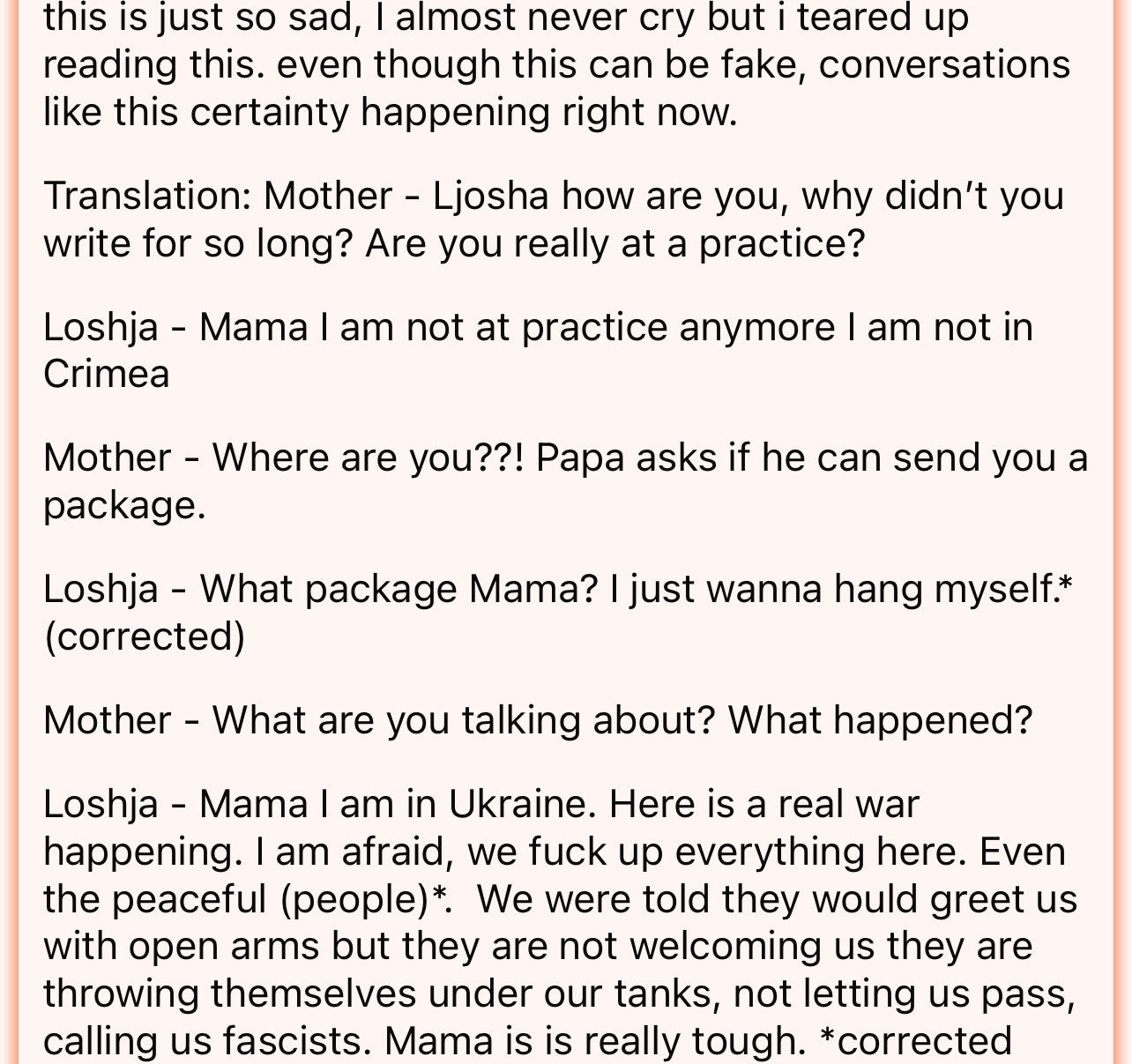

Here’s an image I saw being shared from a community on Reddit:

I don’t read Russian, so I had to look it up to see a translation:

Two things to note here. First, I DON’T READ RUSSIAN! So I’m relying on the credibility of the translator, and I know nothing about said translator. But second, and some giant red flags regardless of whether the translation is true: note the poster’s skepticism but they share it anyway because it’s probably happening somewhere in Ukraine. This makes me want to drink at 9 a.m. The poster is sharing because it confirms what they feel is going on there.

The New York Times even covered this story. They started off reporting that the messages were shared during a United Nations gathering, but note how they report the information but show some skepticism lower in the story:

Ukraine’s military, interior ministry and U.N. ambassador did not respond to requests for more information to help verify the authenticity of the messages read out at the United Nations.

Whatever their origins, the messages allude to an undeniable theme of the war: Fierce resistance by Ukrainian forces has denied Mr. Putin the quick and easy victory Russia appears to have anticipated, while some among Russia’s young military force have been ill-prepared for battle and buffeted by bad morale.

Others can debate the ethics of even sharing this information, but it’s couched in a larger story about memes, viral information, and the information war-within-a-war. That at least adds crucial context, and should give us pause in resharing the images above without any sort of context.

Pets

Note how many layers of credibility you have to go through to just figure out if it’s true. A post about a post about a post. There is a reference to a news source that verified the information, but naturally there is no link to that news.

As it turns out, this information is true, but how exhausting is that? You have to do your own legwork to determine truth, and then you face a choice. Let’s say you think this is useful information and you want folks to know. “Larry The Downing Street Cat For Prime Minister” faced such a choice and instead of posting the link to Sky News, it reshared the post that didn’t confirm the details at all.

Your skepticism should be way up on such a post. The information is true, but before pre-checking it myself I would have bet you it was fake, or misconstrued. In passing on information without links to credible sources, the resharer puts the audience in the same bind it found itself in. Suboptimal.

Woman on the train

Flags abound here. No time stamp, no source, no real proof of anything except she’s wearing blue and yellow (and look, Photoshop could mean that’s fake too). What’s represented could be true, but there is no accompanying evidence. It had about 2500 shares as of this posting.

Why do we do this?

Before you get too smug about “other people” posting things like this, some humility is in order. We have our guard up at times and down at others, and it’s better to understand why things slip through our own nets. Just yesterday I reshared a journalist’s tweet about some information from TikTok. They later retracted it, admitting they didn’t check the source and it turned out to be fake. So I deleted it and unfollowed the journalist, but even if I had more solid grounding to reshare because it came from a journalist, it was on me that I sent it out to my network.

I’d posit there are two reasons why people uncritically share content like the above. The first is an attempt to show what I’d call memetic solidarity, which I’d define as sharing or remixing viral content that thematically is meant to show alignment with a group, point of view, or opinion. In this case we’re talking about a viral image that tracks with our general view of what is going on in Ukraine or what view we support; in some sense the truth is less about the content and more about the show of support via sentiment. It feels super wrong to say it (and in a second I’ll agree with myself), but the truth doesn’t matter here. The second reason is it feeds our desire to feel in control, like something is going right in a sea of chaos. Something positive is a dopamine hit, and we’re eager to share it. It’s an attempt to spread hope.

OK, memetic solidarity. There’s a huge problem with it. While it does signal belief and belonging to a point of view, it’s also a crucial way disinformation and misinformation spread. Images like this wear down our defenses and expose us to similar content from that account that can by virtue of its own slipshod methodology post more insidious and destructive content, and you’d be more likely to encounter it by virtue of how social media algorithms work. Memetic solidarity can be helpful in rallying public opinion in the short run, but it comes with costs. By building solidarity on a crumbling foundation of lies, we open ourselves algorithmically to more and worse lies. These lies ultimately become future ways we frame new information.

Right now I have a lot of skeptical resistance to any images and videos I’ve encountered about Ukraine if they aren’t primary documentation gathered from trusted news sources. None of it, even the personal shares from citizens in Ukraine. Even if it tracks with my viewpoint? Especially if it tracks with my viewpoint. We should be most skeptical of things that feel right to us, a way to short circuit what psychologists call confirmation bias.

My message here: please reshare with care. Even if you fact check something (and you should), it’s better to share what you found from a trusted source than resharing that initial encounter from a random FB page that has information but not the proof. Don’t put your audience in a similar credibility bind by kicking the can down the road. I'd argue we have an ethical duty to not pollute our friends’ social feeds, particularly during times of crisis and chaotic information sharing.

We talk a lot about news trust, but under-discussed is that resharing propaganda and mis/disinformation undermines social trust when a user discovers their friends are not responsible with reposts. Our own credibility is on the line. When I see someone resharing junk, I make a mental note. Sometimes I mute them, sometimes I defriend them if it’s egregious. But even if I keep the connection, it makes me very skeptical of any other information they share. If someone wants to be heard and be persuasive on causes they genuinely work for, they might blow that chance long before by carelessly sharing information on topics they know superficially about.

Two helpful tools I’ll share:

Mike Caufield’s SIFT tool, which is a quick way to assess information you encounter. This is harder to do in longer, more complex stories, but I find it super useful for short social media posts. I use this one in my classes.

Second, I use The Elements Of Journalism on journalistic content, but in a time of citizen reporters on social media it applies broadly. Good reporting is judged by its methods. It shows its work, it verifies before it publishes, it’s an independent monitor of power and serves truth over party or ideology. Journalists are skeptical. So should we be.

Jeremy Littau is an associate professor of journalism and communication at Lehigh University. Find him on Twitter at @jeremylittau.

Another example of memetic solidarity - sharing photos of Zelenskyy in trenches/in military gear - from December 6, 2021 - without making clear that it's NOT a photo from since the invasion started (https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/ukrainian-president-volodymyr-zelensky-visits-the-front-news-photo/1237056843).

Especially when the image is spread widely with generic messages of support and admiration for Zelenskyy, it's potentially misleadingly implying that Zelenskyy is somewhere actually in battle, when the primary sources (his own posts and videos/the accounts of other officials who actually know or interact with him) show he is in Kyiv center/not in combat/theoretically less exposed to battle risk.

amazing to me also how what I call web3 tools are being used ...can you imagine an individual or company able to keep communications going such as Elon Musk has in this situation....or that we can plainly see a 40 mile convoy line of Russian military and the Ukraine govt is asking for private company help in identifying movements of the Russians? Also one fact that has stunned but not confirmed....Russian fatalities are estimated to be 3500...and I can't seem to confirm that but if so in one week 3500 out of 150,000 is unbelievable....as a comparison the entire Vietnam war of ten years had about 50,000 fatalities.....