When the news becomes the noise

Twitter can be a great way to learn and become informed if you build your network well, but it asks a lot of audiences when there is breaking news about things we don't understand.

So, Ukraine. I have been trying, trying, to get my head around what’s going on there for a couple weeks now. Yesterday I admitted to my freshman students that this is a news topic that is so out of my expertise and historical understanding that it’s been a steep climb to understand the subtleties. The basics are easy for me - invading a country and violating their sovereignty is bad! - but understanding why Putin would do this and what our response is and ought to be has been much harder to grok. And I have read a lot about this story.

I won’t bore you with those questions, ones you might have yourself. Instead I want to talk about the problem of understanding, and how news-oriented platforms such as Twitter play a role in making it worse at certain times by virtue of their design and delivery methods.

Everyone’s Twitter experience varies, and it’s a function of how you build your network, a variation of contributor vs. listener (with most users doing more consumption than creation). In that sense, the act of following is really about two things. First, the creators whose ideas and work you want to follow. Second, the amplifiers whose network you want to be exposed to. The second one is an affirmation of credibility in some sense, that you trust as a second-degree relationship a followee’s information diet, and it’s a sneaky critical part of a good Twitter experience.

So most of the time, we live somewhere on the creator-consumer continuum, with the vast majority of users leaning toward consumer. But there are moments such as today when people who might normally just curate and amplify authoritative, expert voices feel the need to chime in, and that has potential to break the entire experience.

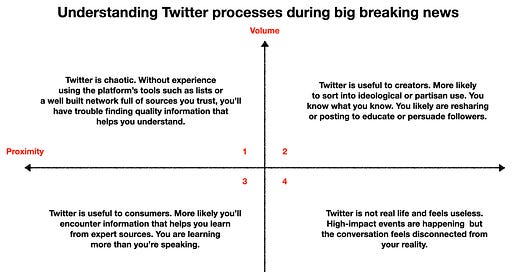

I’d posit that the problem for breaking news events such as Ukraine exists at the intersection of volume (amount of voices entering the square, and the frequency with which they post) and proximity (how you understand the problem either as a matter of physical closeness or prior knowledge). The less proximate you are to breaking news or news out of your usual topics or knowledge base, the more you’re using Twitter to understand the answer to basic questions, and in those moments you really need more expert opinions and voices to offer clarity than you do The Latest Breaking Update. For that kind of person, volume is the enemy. The usual experts are speaking but drowned out by other voices from the Hot Take Industrial Complex or the random users who have no sense of agency on what to do about things so they instead litter your feed with “I Stand With Ukraine” posts even though they largely don’t know what that means.

There are times, of course, that low proximity and high volume are fine. I’d say the less serious the news event is, the more it doesn’t really matter and in fact has outsized value. The ready example I have here is Super Bowl Ad Twitter, the ongoing conversation about ads despite the reality few of us are ad execs, media scholars, or people with deep knowledge about the products at hand. The stakes are so low that the cacophony of infinite voices is fine. Even preferred. It’s fun! But in breaking news of critical importance, particularly when lives are on the line, the waterfall of high volume drowns the meaningful work in a sea of shitposts and Opinions From Dudes With A Keyboard.

The other end of that experience is probably Twitter’s sweet spot, the low volume/proximity situation. There you’re curious and follow good people, and they’re teaching you in breaking news events (or non-breaking news, even) things that genuinely help you learn something but aren’t attracting enough hangers-on who are trying to increase followers or readership with scorching hot takes.

A hastily thrown-together visual of the problem:

It is a generalization, of course, so feel free to peer review me. Your mileage may vary depending on the quality of the network you built, but my sense is Twitter’s real value is in those low volume/proximity moments (Quadrant 3), when your feed is quiet and not filled with frothing reactions by people about things they know vaguely about.

It is tempting to see Q2, the high volume/proximity condition, as good, but really isn’t that the worst of Twitter in some ways? That’s the toxic realm of Twitter ranters, trolls, reply guys and bots. That’s why in those two quadrants it’s useful to denote who it is useful for. If you’re a passive consumer, there are certain conditions that allow you to learn a lot, and it’s almost never when there are lots of tweets being flung around. In some ways, the more you experience Q2 it turns you off to Twitter that deprive you of Q3.

With Ukraine I’m squarely in Q1, and I am not alone. My relationship with news is not unlike many, that instead of going straight to a single publication I’m relying on recommendations for journalists, historians and longreads to understand what’s going on. This is particularly crucial because it’s news from outside the U.S. for me, and so having access to quality foreign correspondents and experts is more needed when I’m on unfamiliar terrain. And in moments like what is happening now, the social media pipeline many of us have built feels very broken because of an inability to cut through the noise.

What we need to understand is that people react to this problem differently. Some dig in deeper or ask for help. I tweeted about the problem this morning and got some recommendations about people and curated Twitter lists to follow. And that’s my network working well for me (again, how you build your network matters!), but notice that this scenario also requires that I have enough presence that my tweeted malaise gets seen by people who have some ability to help me.

In this scenario, many will check out of consuming the news either because they aren’t being heard or because they don’t feel like the equation can be balanced. When they perceive that they have a media diet issue and it feels too hard or impossible to solve, they will avoid it and fall back on ideologues or knee-jerk opinions built on stereotypes (in this case, stereotypes about Russia or Ukraine, or stereotypes about the U.S. political actors lining up on one side or another). This is a problem Walter Lippmann described well in Public Opinion. He noted that we too often are constructing our sense of reality based on superficial engagement with information that invites us to assess and evaluate based on stereotypical thinking rather than deep engagement with and evaluation of information and sources. Stereotypical thinking provides shortcuts for ways of assessing and thinking about information, and it can lead us astray in moments of complexity.

Related, the news is running up against two problems. First, this is a breaking news situation with evolving information, but some of us are struggling still on the geopolitical basics. Getting us caught up without looking like you have stale content is a storytelling challenge, and one that isn’t entirely on the news. In a world of scarce information sources and daily news use, this isn’t as much of a story construction challenge, but that’s not the world we have now. How to fix that without surrendering one’s position as a mass media product is difficult.

Second, the volume problem is buttressed by the entry of misinformation into the square. This is a challenge social networks have tried to counter to varying degrees. Active daily user counts sell ads, and so taking the hammer to bots in particular comes with revenue costs. But we know at this point that Russia has been engaging in this activity for more than a decade now, and right now the reply bots are creating network surges that are making their way into my feed even when I don’t follow them. There also are spoof fake news sources designed to look real that are getting amplified bots and less skeptical users who don’t know how to look for fakers. The difficulty in sorting quality is hard enough, but when I can’t even tell who is creating synthetic content that is an even bigger problem. And it puts a lot on regular users to figure it out, to be aggressive and skeptical when all they want is to use the news.

I like the world of more access and voices that comes with information and publishing abundance. But this is a media dependency moment where we rely more heavily on quality and expertise, and when we feel a bit more out of our depth judging those things without falling back on reliable stereotypes built on partisanship and ideology then it creates an impossible task for users. It shows us that social networks, and news-driven ones such as Twitter in particular, still have some work to do giving us tools to make sense of things.

Jeremy Littau is an associate professor of journalism and communication at Lehigh University. Find him on Twitter at @jeremylittau.

I have found the best source for understanding difficult issues is at the Atlantic magizine ...will email you couple that might help understand....key takeaway for is that 900k Russian troops total almost 200k ground on this invasion...maybe another 100 150k that can relieve in few months..if it is an occupation with resistance going to be very hard....