DALL-E and the childlike wonder of AI learning

Playing with OpenAI's new image generator can teach us about how we learn, and why we get led astray by the things that dazzle us

A while back, I gained access to the new OpenAI project DALL-E (technically DALL-E 2, which is the second generation version of the application). You might have seen the images on your timeline and wondered about them, sometimes showing up as a 3x3 grid of images if someone is using DALL-E Mini or as a set of four images taken directly from the DALL-E app. I’ve posted some examples below to help tell the story I’ve got for today, but if you’re interested in more the #DALLE and #DALLE2 hashtags on Twitter have a lot to pick through. The #DALLEmini hashtag has the mini grids as well.

So what is DALL-E? In a sentence, it’s a web application that takes descriptive text and generates an original image using a neural network enabled by artificial intelligence. Casey Newton wrote one of the best pieces I’ve read on it and I’d encourage you to check it out, but I’ll clip his own description here:

DALL-E — a portmanteau of the surrealist Salvador Dalí and Pixar’s WALL-E — takes text prompts and generates images from them. In January 2021, the company introduced the first version of the tool, which was limited to 256-by-256 pixel squares.

But the second version, which entered a private research beta in April, feels like a radical leap forward. The images are now 1,024 by 1,024 pixels, and can incorporate new techniques such as “inpainting” — replacing one or more elements of an image with another. (Imagine taking a photo of an orange in a bowl and replacing it with an apple.) DALL-E has also improved at understanding the relationship between objects, which helps it depict increasingly fantastic scenes — a koala dunking a basketball, an astronaut riding a horse.

It’s crucial to understand where these images come from. DALL-E is built on the back of millions of images that live on the web, images that have text descriptors such that when the AI crawls online spaces it can see an image that has been named online, and start to conceive of what that object looks like. This piece has a good descriptor:

How does DALL-E 2 know how a textual concept like "teddy bear" is manifested in the visual space? The link between textual semantics and their visual representations in DALL-E 2 is learned by another OpenAI model called CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training).

CLIP is trained on hundreds of millions of images and their associated captions, learning how much a given text snippet relates to an image. That is, rather than trying to predict a caption given an image, CLIP instead just learns how related any given caption is to an image. This contrastive rather than predictive objective allows CLIP to learn the link between textual and visual representations of the same abstract object. The entire DALL-E 2 model hinges on CLIP's ability to learn semantics from natural language, so let's take a look at how CLIP is trained to understand its inner workings.

A less technical example here. How do you know what an apple looks like? At some point (assuming you have had the benefit of eyesight), you connected the word “apple” with a particular object, quite probably at a young age. Picture it in your mind. You see things that are (dad joke alert!) core to what it means to be an apple. It likely has a particular shape, and a stem. What color is it? Your mind apple might be picturing one that is green or red, but notice that the mere suggestion of a color only speaks to a variation of “apple” as you understand it. There is a categorical term “apple” but when you see a green apple you might think “Granny Smith apple.” The point is, look how flexible your learning is. You built a framework for that particular term (and tens of thousands of other terms through learning and experience). If I asked everyone reading this to send me a drawing of an apple, they would all be different but would retain some critical similarities, things we’d call essential to what an apple is. I mean, look out confused Google image search is:

The query I just gave you for an apple is just a single object, but the process of you calling it up wouldn’t be a lot different from what DALL-E does. There is no objective singular image of an apple; this is more art than science, and it’s based on your own understanding of the object. Now notice the critical thing here: the more you know about the object, the more times you’ve experienced it, the better your rendition will be and the closer it’d be to being something that resonated with someone who also knows about that object. This is important for reasons I’m about to get into.

DALL-E has been learning from us. When we post images online, that is source material for DALL-E to figure out what things look like based on a matched set of image and text. Having raised two kids from young ages, this type of AI learning is remarkably similar to how my children assembled concepts from infancy. Repetition, examples, reinforcement or correction … that’s how we come to know what we know.

Now what DALL-E does is more complex than that. It’s not just giving you single objects, but also multiple objects together, ones that you’re not going to find in a reference image online. As Newton noted in the quote above, it’s not just objects but other things like scene and mood, the ability to present as a vibe (things you will see in examples below). These really are images that lack any kind of reference point online, so the work the AI is doing here really is about connecting multiple concepts into a whole and asking you if that works.

I share Casey’s enthusiasm for DALL-E because it feels like a throwback to the early days of the internet, when we had tools with lots of potential but no specific practical use at the outset. More simply, we have technology that people are just playing with at the moment rather than using as a tool for a designed purpose. That is a much more open playing field that allows user imagination to help define what’s next. Plus it’s just a lot of fun.

I’ve been playing with DALL-E for some time now and wanted to share both my own process and what I’m learning from using the tool.

So here we go.

The interface for generating an image is sparse:

Kenobi and Vader bonding over a Hawaiian pizza was the first thing I tried. What DALL-E asks of you up top is to think of something that has no image context. You wouldn’t ask for the Eiffel Tower, for example. OK, you could, but why would you other than to see how DALL-E tries to generate it?

Attempt 1: Obi-Wan Kenobi and Darth Vader sharing a ham and pineapple pizza

Terrifying. Notice that at times they are toppings themselves. Only in the third (and possibly the second one) are they dining together. Also for some reason (because I didn’t prompt a style in this query) it decided to portray the people as something akin to claymation minifigures. I learned from this and my next query below that if you don’t give DALL-E the style for rendering it, it’s going to guess.

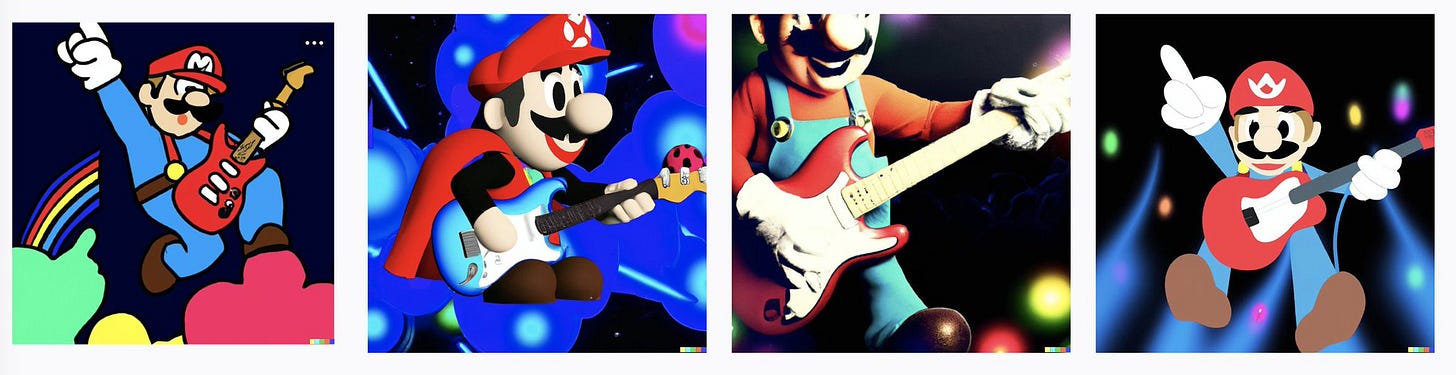

Attempt 2: Super Mario playing guitar at a rock concert

See what I said about style? No claymation here, but I got a bit more variety. The first and fourth images are more 2D cartoon, but the middle two are three dimensional.

I want to note something else about these images. Remember what I said about apple not having an objective look? Think about your reaction to the Google search strip above and compare it to your reaction of how Mario is formed. Are you less satisfied with the Mario rendition than the versions of an apple that Google served up, even if it wasn’t the color you pictured?

My guess is you are, and you should be. One of the things about this particular search is Mario has something more akin to an objective form. The images here get the colors right, and the mustache. It mostly gets the hat right, but notice only one of them has the iconic M on the brow. One of my takeaways from this, one of my early queries, is that DALL-E is more likely to disappoint me or produce something I’m resistant to if I have a much more solid idea in my head of what the image is supposed to look like. Note in this case, I don’t have a particular look for the scene - playing guitar at a rock concert - but I do have a much more firm version of what Mario himself ought to be. The one I like most in this array is the third one, and it shouldn’t be a surprise. It doesn’t have a problematic version of the hat and contains much of what I’d call core to the Mario look. This is the difference between a categorical version of a concept and a specific iteration. In the case of an iconic image or character, we are likely to have a specific vision based on an iteration.

I’ll come back to this point in a bit, but wanted to raise it now because it became the basis by which I experimented after that.

Before we do that, I asked my 11-year-old son to give me some language and we generated something from his imagination.

Attempt 3: Iron Man eating a Big Mac at McDonald's

I’m showing this because there’s another interesting wrinkle on DALL-E that lets you teach it what you want. Each image, when you mouse over it, gives you a menu that lets you tell DALL-E if a particular image meshed with what you wanted. In this case, you can generate variations of a particular image in the set. My son picked the second one.

Notice what it “learned.” What the new set has in common is Iron Man is facing the viewer, unlike the other four. He also is holding product in his hands in all of them.

But of course this has the same problems of the Mario one in some ways. Most of us have an image of what Iron Man’s costume looks like, and this isn’t it. The really interesting thing is that in both this and the Mario examples, you look at it and know exactly what it is. So in that sense it’s a success, but our brain probably interprets that as incorrect even while we can understand it. Is that success or failure? It depends on what the goal was. I would liken this to you having a rough mastery of another language and traveling to another country. You could mostly communicate. Certainly enough to get by and have understanding you need to go about your business. But nobody would mistake you for someone who has mastered the language, and you’d be marked as an outsider.

These last two examples got me thinking about how to dream up images that I don’t have a real reference point for, one where I’m thinking more about categories rather than a specific iteration.

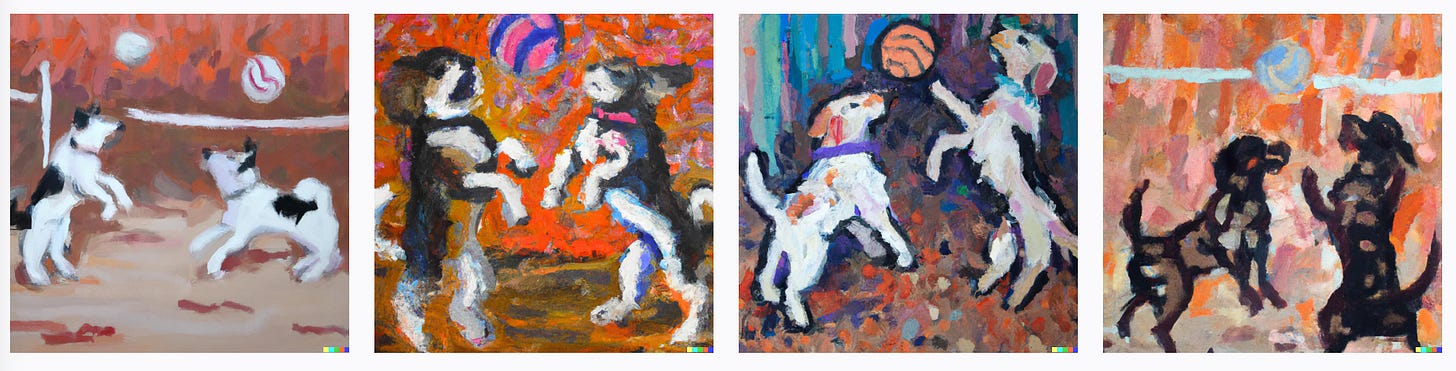

Attempt 4: An impressionist painting of dogs playing volleyball

This is the first time DALL-E dazzled me. But notice what happened here. I asked it to give me an image of something where I had much lower expectations, and boy did it deliver. I have nothing to nitpick here. No “that isn’t a dog” or “that isn’t impressionism.” I have no concept of dogs playing volleyball, and I vaguely remember the concept of impressionism from college art history class. This seems to work.

So this is the opposite of my Mario takeaway. The less iconic the object, the more imagination-driven this, the more likely it is that DALL-E is going to give me something that blows me away.

This is, plainly put, a product of my own bias and ignorance. The less I know, the more drawn in I am, the more I feel DALL-E’s brilliance.

I did a few more to play with this realization.

Attempt 5: Dee Snider as a film noir detective

Attempt 6: A cubist depiction of Mickey Mouse roping cattle

Attempt 7: Macbeth being performed in a snow globe

And just for fun, one more:

Attempt 8: Space aliens invading Lehigh University

I definitely like the first and fourth Lehigh one, as those do look like Lehigh buildings. Notice the first one, the front looks a bit like our much beloved Linderman Library.

Some takeaways

Learning how to use this tool has been an interesting insight into how humans process information.

As I noted before, the more context and expectation I had for an image, the more critical I was of it. But that also reveals the contradictions of language. Even the imperfect images, there was nothing lost in communication. But that is a stop-short of accepting the image as valid or true.

I’ve been thinking about this in the context of where I normally research and teach, and that is online spread of misinformation. In particular, the places where DALL-E awed me were a bit scary to experience for the first time, because I imagined myself as a Qanoner who has low resistance to information put in front of them and becomes enthralled by the connections it attempts to make. This isn’t moral panic here, it’s awareness. Our brains our intrigued by novelty and the unexpected. Think about a subject where you know a lot. You’re more likely to be critical of news or imagery that doesn’t fit what you know. Bear in mind, what you know could be wrong or incomplete, but my experience here gave me a bit of empathy for people who encounter a fact check and don’t believe the facts that dispute their own view of the world.

In my field, we talk about how reality is something we socially construct from lived experience plus the media we consume. We have mental frameworks and ideas about places we’ve never been and experiences we never witnessed because of media, and those things come to stand for truth in some sense. “Reality” for us is a mix of these things, and very hard to challenge. Walter Lippmann famously demonstrated this in his 1922 book “Public Opinion,” where in a segment about India he stopped and noted that many readers had an image of the Taj Majal in their head while reading. It’s not much different than my apple example.

We use image stereotypes to stand in for the thing because it allows us to get to the heart of the information. Sometimes these stereotypes can be useful mental shortcuts, but sometimes when they come to stand for the thing for all time, they can become less useful and in some cases dangerous. But past that, I wonder if this is another layer to Daniel Boorstin’s observation in “The Image”:

The image, more interesting than its original, has become the original. The shadow has become the substance.“

Boorstin was writing about media imagery, and how in particular when we are experiencing something entirely through media images it becomes the thing we revere. Digital images of the Mona Lisa become the way I experience it, for example, such that I’m let down when I see it in person.

I wonder if DALL-E is peeling some of that back for us. In challenging me to think about what the “essence” of Mario or Twisted Sister’s Dee Snider is, it’s inviting me to wonder whether the vibe that makes communication possible is more important than it being technically accurate in all phases. I could show that image of Iron Man to people and ask them what it was, and they’d probably get pretty dang close to describing my text query. That is DALL-E being successful if the goal is to communicate; it’s only a failure if we prize precision above all else. Think about different types of communication modes that prize precision (such as news) vs. understanding of broad strokes (interpersonal, at times, or casual chit-chat) and you’ll see places where DALL-E could help us create greater understanding. Sometimes the details don’t matter, and sometimes they do. But precision isn’t just about intended message, as we learn here. It’s also about precision in the mind of who’s imagining things. If my goal is to dream something up, DALL-E’s take on volleyball-playing dogs is an extension of my imagination.

As I said earlier, this is why I’m excited about this project. DALL-E is learning from us, but it also has a lot to teach us about the ways we’ve learned to see the world. It can challenge us if we get past our human-centered ways of seeing the world and accepting a different version of reality. Perhaps useful, perhaps not. But it’s a different point of view and lens of how we understand the world.

You have to get on a waitlist to use DALL-E 2, but you can use DALL-E Mini now. Play around with it and tweet me some examples.

Jeremy Littau is an associate professor of journalism and communication at Lehigh University. Find him on Twitter at @jeremylittau, or just type his name into DALL-E and stare at that all day.

https://dontcountusoutyet.substack.com

here is link to our newsletter....just starting to reach out to people to subscribe that are important....Ann at Adobe just signed up...maybe way to recommend yours and you recommend ours