The *real* internet regulation fight

Congress is set to take up the hot potato issue of internet regulation. But the debate to watch is less about policy proposals and more about the incentives driving which companies take which side.

Welcome to the first issue of The Unraveling, a weekly brainpurge that will cover current media issues and internet culture with a mix of theory, scholarship, and practice. Because you really don’t want to see me dancing on TikTok.

—————

With a new administration taking power in the United States, a lot of focus these days is on exactly what newly sworn-in President Biden will do with the debate over the government’s role in regulating internet platforms. You might have heard about this obscure, under-the-radar story: after years of resisting criticisms, Twitter, Facebook and a few others deplatformed a sitting President back in early January after the Capitol insurrection.

Oh wait, did I say it was under the radar? I meant it’s been one of the bigger things you can find people screaming about on Twitter now that Donald Trump isn’t driving most of the discussion agenda online.

There are a lot of layers to the regulation debate and why this is surfacing now. The lay version could be summed up as:

Digital self-publishing platforms have amassed a lot of audience and power in the past 15 years.

That power has come at the expense of traditional outlets whose business models were built on near-monopoly of audience due to the cost and difficulty associated with pre-internet publishing and broadcasting.

This emerging power online has become concentrated to a few platforms (namely Facebook, Twitter and YouTube) such that their policies about who’s allowed to join and speak have genuine implications on the wider discourse.

Even if the platforms play ball, tech companies such as payment processors, app stores, or web server services such as AWS have the power to alter policy on social platforms that need to distribute their product or outsource on infrastructure.

Something something free speech.

The first four bullets are invariably true to some degree. The last one is disingenuous. People invoke the First Amendment (doesn’t apply here) or the marketplace of ideas (as if a debate was truly happening in algorithmic echo chambers). They also ignore that anyone with some technical skill could build something; the problem isn’t one of publishing (speech!) but rather one of distribution, which is some weird expectation that people have a right to be listened-to.

Also burning is a question about whether what happened to Trump is THE rule or a specific use-case exception. This is a policy question, but it’s also a type of concern trolling that is more rhetoric than reality. For example, Twitter isn’t banning people for advocating for deregulation and tax cuts—they are not going after conservatives despite rhetorical claims to the contrary. They’re deplatforming conspiracy theorists and people spreading threats or disinformation that puts lives in jeopardy on the theory that, well, you can say what you want but we don’t have to hand you the mic.

Banning Trump and QAnon devotees is the right call, but I’m also uncomfortable with the concentrated power platforms like Facebook and YouTube have relative to peers. That doesn’t mean the solution is easy, and it certainly doesn’t lend itself to a binary choice between heavy regulation or no restrictions. Some of the problem is audience choice. We flock to where the people are, unless we don’t like the people we’re with. Same as it ever was.

Most of the policy to be made in this regulation discussion is going to center on Section 230, a decades-old U.S. law that exempts publishing from platforms from liability even if they do some moderation of content. When I say liability, think: libel, slander, someone planning a terrorist attack, etc. But 230 is a frequently misunderstood bit of policy at the public level (read a good explainer here) and it’s hard to know whether politicians misstating 230’s aims are doing it in bad faith for political gain or are just really dense. Probably both! But don’t lose sight of the cynical motivations by some actors here, that some of this is rhetorical nonsense that exists to get people riled up and donating to political campaigns.

Regardless, it’s pretty clear that a 230 repeal, as some Republicans are arguing for, would predictably lead to more limits on expression; getting what they want would be decidedly bad for their self-interests. The minute Twitter or Facebook become liable for your crazy uncle’s shitposting, they are going to limit anything that might get them sued. That’s a pretty rational choice, one that most of us would make.

What will follow is a world where playing it safe lets you keep your account. It’ll all be rainbows, puppies, and coded language again. How discourse-y!

But given all that, my real insight into the regulation debate is we’re watching the wrong TV show, and thus missing the drama that will determine the course this all takes beyond the posturing politicians do for talk radio and the cable news jet set. I do worry about a 230 repeal, or even a severe weakening, because 230 has allowed new and unconsidered ideas to flourish in a publishing world that lacks the usual scarcity barriers. Black Lives Matter, for example, has a much more frictionless platform for publishing, networking and spread because of 230. Liability has a way of causing publishers to clamp down on things that aren’t going to get them sued, out of a desire to play it safe. You can make policy to address Q conspiracy spread, but groups that are not a liability likely will get caught up due to the blunt-force nature of policy at the scale of a YouTube or Facebook.

But there’s a media economics angle beyond liability we are largely ignoring, and one that will have a powerful influence on policy as big media brands line up and take sides, ready to toss pallets of cash at politicians looking toward the next election.

Many of you already know the story of media consolidation that has been happening globally for decades, particularly here in the U.S. where many of the most influential media companies are located. When I was a college student in the ’90s, we talked about the “Big Ten” conglomerate companies that owned the vast majority of media properties in the U.S. By the time I started teaching at Lehigh in 2009, I was talking about the Big Six that owned 90% of U.S. media. Now it’s the Big Five. These are megaconglomerates, made up of companies that are horizontally integrated in a sector (think: they own lots of newspapers) and vertically integrated across sectors (think: they’ve spread their risk by playing in a lot of sectors, such as tv, radio, print, internet).

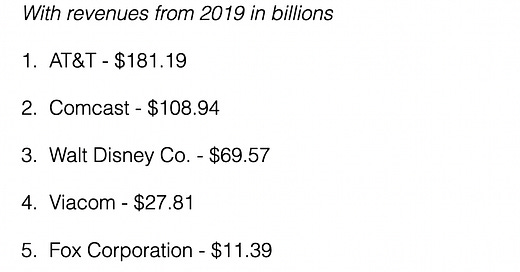

What’s been happening for decades now is that the bigger conglomerates have been gobbling up the smaller ones, such that most of what we think of as media (news, entertainment, social) is concentrated in the hands of a few players. The result is an oligopoly that controls most media corporations in an industry that generates about $2 trillion annually, and that small circle of control has outsize role in policy. To wit, from one of my class slides:

I mean, if you’re worried about limits on expression, it seems nonsensical to me to repeal something like 230, which has allowed for competition to flourish against those conglomerates, while ignoring the outsize power of these concentrated media companies. Yes, I worry about the outsize power of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. But in some sense, despite their problems they are a type of check on the power of companies like Disney, which are in devour mode and which have enough control to turn everything bland. Let’s take that last slide and add some of those new players:

The companies in red are U.S.-based tech companies that dabble somewhat in content, the ones in blue are global companies not based in the U.S. Click on the footnote marker to understand some of the nuance here.1

Broken down like this, you can see on the some of the emerging players in the debate. The companies in black, those Big Five, are traditional companies creating and distributing media content by traditional means. They are largely not thinking much about having to host content produced by their user base; they might have some user content, but their businesses are vast and diverse. Many of the ones in red, though, are heavily dependent on user publication. What kind of business does YouTube or Facebook have without user-generated content (UGC)? Microsoft is subtly subject to some of this too, with stakes in UGC services like Skype or online video gaming portals. Amazon owns AWS, which provides an infrastructure backbone to a lot of the social platforms that host UGC.

What you need to understand from those two slides is the first one is a set of companies that have traditionally controlled the board when it comes to media ownership, and thus profits. The second are upstarts. Other than Apple and Microsoft, which have seen their prospects rise and fall over the past four decades and really weren’t playing in the media space much prior to last decade, none of those companies existed prior to 1994. They are “new money” in world of trillions in media revenue.

Why does this matter? Because reforming regulation for the internet and only the internet comes with winners and losers, and unlike a legacy media world where regulation of one industry hits all players in similar ways, the kinds of reform being bandied about now will not be equal opportunity. Section 230 is an example. It’s mainly a focus on the liability from a self-publishing audience, at least in the rhetorical posturing we see from politicians and ideologues right now.

Netflix is an internet company, but they are not of the same kind as Facebook and as a result they have a different set of interests and incentives in this debate over regulation. Disney might have some legal exposure in a 230 repeal from things like internet comments on an ABC news story, but that’s a concern that can be addressed by just getting rid of comments and some minor tinkering at the edges of its vast array of products. Disney will be fine. A 230 repeal is an existential threat for a service such Facebook, though.

Revenue, diversification and business models are a big part of how these companies would view reform. The other piece is what is driving the economics of media use right now: attention.

Put simply, a Facebook or YouTube diminished by 230 repeal or major reform potentially are less interesting places for users. Social platforms have been able to amass such power because they have been able to attract and keep audience at a scale once enjoyed by the conglomerates, one that attracts advertisers away from the legacy players by virtue of stealing audience share. If YouTube is bland or uninteresting to people because it’s not keeping your attention, you’re not going to quit using media. You’re going to go somewhere else. Maybe it’ll be more time bingeing on Netflix or Amazon video. The legacy players hope you’ll return to what they’re distributing.

Put that way, the picture is a lot clearer. You can picture a world where traditional players like AT&T or Comcast are lobbying for much more stringent-yet-surgical internet regulation that focuses on liability over content produced by the masses. That puts social media companies as uniquely in the crosshairs of any reform. The conglomerates are built to survive a world where most of the reform is about UGC liability, but many of the tech platforms will face much more difficult challenges. Even if it doesn’t kill your platform, it will alter it in ways that are meaningful and noticeable to your user base. The result is we end up in a world that looks a lot more like the media landscape at the dawn of the public internet in the 1990s than it does the sprawling self-publishing ecosystem of 2021. Legacy players would see some of their power restored by a reinflation of the monopoly bubble.

I mention all this because you’re going to see a lot of news coverage on this issue in the next year that references “the media” or “platforms” as if they are one, as if their interests are aligned. They most certainly are not.

The ownership situation in the U.S. is much more complicated than that and the content origins are much more varied, which increases the odds that something is going to change in policy once these companies figure out where to send the check and politicians have ample time to add up the funds in the appropriate “change” or “status quo” columns. Disney gave $19.3 million to politicians in 2019 and spent another $4.6 million on lobbying. Yes, a fraction of their $69 billion in revenue, but they have the deep pockets to buy results. Journalism’s gift to me was to tell me to follow the money, and the money says don’t bet on inertia.

Still, there is too much cash being thrown around for us to assume it’ll flood to one side; the best hope here is they cancel each other out and the U.S. government will do what it routinely does about hot-button issues: nothing. But I have less hope in that, because the companies on the status-quo side are the ones in the hot seat right now. Nobody’s really mad at Disney’s power right now. Well, except me, because Rise Of Skywalker was horrible. But everyone seems to be mad at Facebook and Twitter, regardless of ideology and there are some things the soft power of political donations can’t fix.

The companies to watch are ones like Apple. They make the hardware many of us use to access this wide world of content we have no time to consume, but they really haven’t dabbled directly in UGC much (other than Ping, may it rest in peace, which fulfilled all our dreams of knowing a random celebrity’s iTunes music library).

But Apple does have a stake in seeing companies with social apps flourish, because those apps are a type of raison d'être for having an iPhone unless you’re one of those monsters who enjoys talking on the phone. You could say the company benefits downhill from a world with Section 230, but you could also see a world where they flourish if power re-concentrates to traditional media companies. Apple has a strong libertarian streak that would make it a natural to oppose something like 230 repeal, but it also has strong incentives to bet on the winner. Where they make their bets might be a sign of where this whole thing is going, or which way the wind is blowing.

A couple technical notes on that slide. The ones in red are U.S.-based companies that largely are tech companies or distribution platforms. Netflix probably produces the most original content, but they have long primarily been a distribution company for content others make. Same for the others in that category. The companies in blue are not U.S.-based, and their story is a bit more complicated. Tencent and Baidu are located in China and media ownership is structured such that they are playing in a lot of spaces such as commerce and AI that would be separate businesses in the U.S.